Featuring over 200 paintings, sculptures, drawings, performances, and immersive installations, this exhibition is, in Teo's words, an opportunity to discover new ways to encounter and think about art through a lateral comparison with art from Latin America; consider how tropes of the tropics across the two regions were shaped by a confluence of Modern art, mass tourism, and popular culture; and reflect on how artists engaged and resisted these stereotypes.

With Teo, curators Shabbir Hussain Mustafa, Cheng Jia Yun, and Qinyi Lim have developed an exhibition of three distinct sections: 'The Myth of the Lazy Native', 'This Earth of Mankind', and 'The Subversive'. It includes artists from the early 20th century to the present; from Brazil and Mexico to Singapore, Malaysia, Burma (Myanmar), Indonesia, and the Philippines, drawing out threads of connection and exchange. Each thematic title is a literary reference, reflecting the connections between writers, poets, architects, and artists engaged with decolonial ideas.

Exhibition view: Tropical: Stories from Southeast Asia and Latin America, National Gallery Singapore (18 November 2023–24 March 2024). Courtesy National Gallery Singapore.

A few weeks after the opening, I spoke with Teo from São Paulo about the exhibition's comparative approach to art from Southeast Asia and Latin America, framed by struggles against colonialism. We discussed the radical concrete and glass exhibition displays designed by Italian-born Brazilian architect Lina Bo Bardi in the 1960s, print media, self-portraiture, interactive and immersive artworks, and interpretations of the term 'tropical'.

CBHow did you set out to approach this exhibition?

THMThe four of us began this project by thinking about the notion of 'the Tropics', and particularly how early images of Southeast Asia and Latin America came about. We focused on the shared solidarities and experiences that artists and people of Southeast Asia and Latin America experienced across the 20th century, connections that were both real and felt.

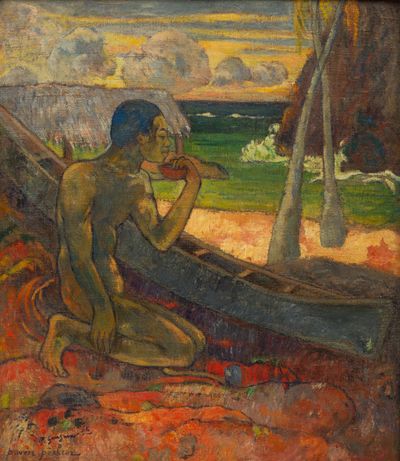

Paul Gauguin, Pobre Pescador (Poor Fisherman) (1896). Oil on canvas. 75 x 65 cm. Gift of Henrik Spitzman-Jordan, Ricardo Jafet and João di Pietro. Collection Museu de Arte de São Paulo Assis Chateaubriand. Courtesy of Museu de Arte de São Paulo Assis Chateaubriand. Photo: Eduardo Ortega.

CBYou mention early images of Southeast Asia and Latin America. Can you discuss specific images you have included in the exhibition?

THMWe looked at Paul Gauguin's work—not so much as a starting point, but an inflection point. Gauguin travelled to Tahiti in 1891 and after that trip, unleashed upon the world images that continue to perpetuate stereotypes of half-dressed natives lounging on beaches.

The scenes were fantasies that he pieced together, and we can see how these images became pertinent in the story of Modern art. We go from Gauguin's images to the primitivism of Picasso, and we can trace their reverberations across the 20th century. It was these kinds of portrayals that many of the artists in Tropical spoke to.

Left to right: David Alfaro Siqueiros, Presságio (Angélica Arenal de Siqueiros) (Omen [Angélica Arenal de Siqueiros]) (1950). Vinyl on fibreboard. 100 x 83.5 cm. Gift of Don Emílio Ascárraga. Collection Museu de Arte de São Paulo Assis Chateaubriand. Courtesy Museu de Arte de São Paulo Assis Chateaubriand; David Alfaro Siqueiros, Angústia (A Mãe do Artista) (Anguish [Artist's Mother]) (1950). Vinyl on fibreboard. 95 x 76 cm. Gift of Don Emílio Ascárraga. Collection of Museu de Arte de São Paulo Assis Chateaubrian. Exhibition view: Tropical: Stories from Southeast Asia and Latin America, National Gallery Singapore (18 November 2023–24 March 2024). Courtesy National Gallery Singapore.

CBThe show's first section is titled after Malaysian sociologist Syed Hussein Alatas' 1977 book, The Myth of the Lazy Native, which critiques the colonial construction of Malay, Filipino, and Javanese natives between the 16th and 20th centuries. How do the artworks explore this myth?

THMSeveral works engage with the representation of colonial subjects. We can look at Indonesian artist S. Sudjojono or Mexican artist David Alfaro Siqueiros, who, instead of painting idyllic scenes of colonial life, captured the experience of family members, freedom fighters, fellow artists, and everyday people. They painted these figures in earnest, as a form of resistance against the external image of the tropics that had taken root by the early 20th century.

Exhibition view: Tropical: Stories from Southeast Asia and Latin America, National Gallery Singapore (18 November 2023–24 March 2024). Courtesy National Gallery Singapore.

There's an affectionate portrait by Sudjojono in the exhibition, of his wife as an expectant mother. We see his focus on the everyday and elevating individual experience. There are similarly socially engaged works by the artist in the exhibition. In one, an artist stands with his paintbrush amid a busy cross junction. He symbolises the desire for revolution and change.

There are palm trees and pineapples, but there's also this tension between the tropes of the tropics and an underlying line of resistance that artists managed to walk quite elegantly.

Alongside that, we have iconic figures such as Tarsila do Amaral. In a work on loan from Museum of Modern Art, Rio de Janeiro, the lazy native is depicted as a fruit seller surrounded by an incredible array of tropical fruits. But the expression on his face is—and Alatas uses this word—'indolent'. He's looking at us, and he doesn't look very happy to be there, but at the same time, do Amaral surrounds him with these beautiful, warm blue, green, and yellow tones. There are palm trees and pineapples, but there's also this tension between the tropes of the tropics and an underlying line of resistance that artists managed to walk quite elegantly.

Tarsila do Amaral, O vendedor de frutas (The Fruit Seller) (1925). Oil on canvas. 108.5 x 84.5 cm. Gilberto Chateaubriand Museu de Arte Moderna do Rio de Janeiro Collection. Exhibition view: Tropical: Stories from Southeast Asia and Latin America, National Gallery Singapore (18 November 2023–24 March 2024). Courtesy National Gallery Singapore.

CBYou have said that Tropical rests on the notion of stories and their power. Did you come across interesting stories about the relationships between artists in the show?

THMWe asked ourselves, what were the connections between these artists? One story is that the Filipino artist Victorio Edades met with Diego Rivera in New York in the 1920s to discuss muralism. We couldn't verify this and it likely never happened, but the story continues to be told and speaks about the yearning for connection and solidarity.

Looking at works by artists like Edades, and tracing the story of how muralism became a powerful tool for artists in the Philippines to look at the past and to the future of a newly independent country, we see their connection to the ambitions of muralists in Mexico.

Victorio C. Edades, Galo B. Ocampo and Carlos "Botong" Francisco. Mother Nature's Bounty Harvest (1935). Oil on canvas. 257.5 x 273 cm. Private collection. © Armin Christopher E. Cuadra. Exhibition view: Tropical: Stories from Southeast Asia and Latin America, National Gallery Singapore (18 November 2023–24 March 2024). Courtesy National Gallery Singapore.

CBWhat does that connection look like?

THMThere's a key work in the exhibition, Mother Nature's Bounty Harvest, which was painted in 1935 by Edades and two other artists, Botong Francisco, and Galo Ocampo, and is representative of the large-scale public murals they painted in Manila.

Looking at how they formed their figures—in these extremely solid, rounded ways with flat planes of colour—and tying that to stories of Filipino history, we see remarkable similarities with what Mexican artists did through paintings by Diego Rivera and David Alfaro Siqueiros, which are also on display in the exhibition.

Diego Rivera, La molendera (Woman Grinding Maize) (1924). Oil on canvas. 90.5 x 117.2 cm. Collection Museo Nacional de Arte, Mexico/INBAL, Secretaría de Cultura. © 2023 Bank of Mexico Diego Rivera & Frida Kahlo Museums Trust. Av. May 5. No. 2, col. Center, alc. Cuauhtémoc, cp 06000, Mexico City. Exhibition view: Tropical: Stories from Southeast Asia and Latin America, National Gallery Singapore (18 November 2023–24 March 2024). Courtesy National Gallery Singapore.

We also looked at real instances where artists met. One example is in London, where David Medalla co-founded Signals Gallery in the 1960s, where many artists from Latin America including Lygia Clark and Hélio Oiticica were invited to exhibit their works.

Through these stories, we see how artists sometimes met and sometimes didn't, but there's this fantastic circulation of ideas, writings, and images to which many referred and responded.

Hélio Oiticica, Tropicália (1966–1967; remade 2023). Wooden structures, fabric, plastic, carpet, wire mesh, tulle, patchouli, sandalwood, television, sand, gravel, plants, birds, television, and poems by Roberta Camila Salgado. Dimensions variable. Collection Projeto Hélio Oiticica. Exhibition view: Tropical: Stories from Southeast Asia and Latin America, National Gallery Singapore (18 November 2023–24 March 2024). Courtesy National Gallery Singapore.

CBArt in the 20th century was informed in radically different ways by art made in other locations, compared with art made today, considering digital access. What other means of exchange did you identify?

THMWe tend to think of the current digital landscape as an over-saturation of images, but print media played an incredibly similar role in the 20th century in circulating images and ideas. To go back to Gauguin, after he passed, Museum of Modern Art in New York held their first exhibition in the 1920s, which included a presentation of Gauguin's works.

Thereafter the entire museological complex of the reproduction of Gauguin's images began; think about museum catalogues, art periodicals, and magazines. In the zone called 'Library of the Tropics', we trace this circulation of images through an accumulation of books on Gauguin and his time in Tahiti, presented alongside what we see as a twin, the island of Bali, which in the 1920s also saw this onslaught of images of the exotic.

Eugenio Espinoza, Not titled (Circumstantial [12 coconuts]) (1971). Acrylic on unprimed canvas, coconuts, and rope. 150 x 150 x 25 cm. Collection of the artist. Exhibition view: Tropical: Stories from Southeast Asia and Latin America, National Gallery Singapore (18 November 2023–24 March 2024). Courtesy National Gallery Singapore.

Bali became an incredible destination for people like Charlie Chaplin, Mexican artist Miguel Covarrubias, and German artist Walter Spies, who all travelled there perhaps seeking the same vision of paradise that drew Gauguin to Tahiti.

We were thinking through 'the Tropics' not just as a place or in a geopolitical sense, but as a space for making, thinking, and being. Through that process, we landed on 'tropical' as an attitude.

That incredible circulation of images, not just of exotic tropes, but Modern art in general, were incredible resources for artists from both regions. This was also happening alongside a literary track. Writers and poets—Octavio Paz, Jorge Luis Borges, Rabindranath Tagore—were heavily translated into Spanish; they were all part of a circulation of ideas that presented alternative models of thinking and working through the experience of colonialism. In our exhibition, we think about how these filtered through different types of art and expression.

Dolores Zinny for Zinny Maidagan, Tigresses. Handsewn banners and synthetic leather; Juan Maidagan for Zinny Maidagan, Trees. Acrylic on canvas, rubber, and coconut coir rope; Dolores Zinny and Juan Maidagan, Vientos Alisios (Trade Winds) (2023). Digital print on organza and canvas. Collection of the artists. Commissioned by National Gallery Singapore. Exhibition view: Tropical: Stories from Southeast Asia and Latin America, National Gallery Singapore (18 November 2023–24 March 2024). Courtesy National Gallery Singapore.

CBI often think about the role of writing in creating this imagistic setting. Are there texts exhibited physically in the show?

THMEach of our section titles is named after iconic Southeast Asian texts, which informed starting points for our thinking. The first section, for instance, 'The Myth of the Lazy Native', is from a text by Malaysian sociologist Syed Hussein Alatas, written in 1977, a year before Edward Said's Orientalism. So the literary is embedded into the exhibition.

We also had fun collecting books on Bali for the Library of the Tropics, from Lonely Planet travel guides to Elizabeth Gilbert's Eat Pray Love (2006), to art historical, critical, and anthropological texts. Artist manifestos also hang in the space. These texts have incredible resonance across Southeast Asia and Latin America. The periods don't run concurrently because of the nature of colonial histories, but you can see synergies among the artists' manifestos.

Exhibition view: Tropical: Stories from Southeast Asia and Latin America, National Gallery Singapore (18 November 2023–24 March 2024). Courtesy National Gallery Singapore.

CBHow can visitors come away with a sense of what 'the Tropics' meant at that time? What were artists putting forward that 'the Tropics' were?

THM'The Tropics' and 'tropical' are such slippery words; they come with many possibilities. We were thinking through 'the Tropics' not just as a place or in a geopolitical sense, but as a space for making, thinking, and being. Through that process, we landed on 'tropical' as an attitude.

For instance, Hélio Oiticica said that 'the Tropics' are 'much more than parrots and banana trees'. Similarly, Malaysian artist-poet Latiff Mohidin invokes tropika, the Malay equivalent of Tropicália and 'tropical'. He talks about 'the Tropics' as a place with an incredible propensity for both growth and destruction—the heat and entropy that are at the root of creative generation.

Hendra Gunawan, Tjitji (1949). Oil on paper laid on masonite. 64 x 49 cm. Collection National Gallery Singapore. Courtesy National Heritage Board, Singapore.

CBYou mention the tension between something at once constructive and destructive. In 1928, in Brazil, writer Oswald de Andrade published Manifesto Antropofágo, based on a metaphor rooted in cannibalistic practices (anthropophagy). This manifesto brought forward the idea that consuming techniques and influences from other countries (mainly European) and 'expelling them anew' would generate a strong national identity in material culture. How does this come through in the artworks?

THMIt's such a productive way of thinking. Andrade's is one of the manifestos that we have on display, right next to do Amaral's painting and across from another manifesto, from Indonesian artist S. Sudjojono. It refers to Modern art as 'a shipwreck'.

Exhibition view: Tropical: Stories from Southeast Asia and Latin America, National Gallery Singapore (18 November 2023–24 March 2024). Courtesy National Gallery Singapore.

The implication is that artists in Indonesia will be the ones to take the project of Modern art forward. He wrote this manifesto in response to a Dutch art critic who, after attending an exhibition of Indonesian painters, wrote a very incisive article that said what he had seen were just imitations of Western art.

This question of influence and representation is at the core of what we are looking at across the exhibition. We're also cognisant of not putting this in a binary—'Southeast Asia and Latin America versus Western European Art'—that's not what we're interested in, we're interested in having lateral conversations.

Frida Kahlo, Self-Portrait with Monkey (1945). Oil on masonite. 60 x 42.5 cm. Collection Robert Brady Museum. © 2023 Bank of Mexico Diego Rivera & Frida Kahlo Museums Trust. Av. May 5. No. 2, col. Center, alc. Cuauhtémoc, cp 06000, Mexico City. Exhibition view: Tropical: Stories from Southeast Asia and Latin America, National Gallery Singapore (18 November 2023–24 March 2024). Courtesy National Gallery Singapore.

CBSelf-portraiture is a genre that precedes the 20th century. It explores both introspective exercises on behalf of artists and public identities they wanted to commit to and comment on. In the age of selfies, we understand how much of this exercise is a construct as opposed to an unbiased practice. Why was self-portraiture valued?

THMAs you rightly point out, self-portraiture has an incredibly long and steeped history, but I think that artists in Southeast Asia and Latin America adopted the model with a great sense of empowerment—as part of a broader collective story about reclaiming a place for themselves within the story of Modern art.

In this show, we look at how these artists' self-representation and presentation intersected with a socio-historical context as they experienced postcolonial, independent nation-states, and how art questioned and blurred the lines around identity and national identity at the time.

Exhibition view: Tropical: Stories from Southeast Asia and Latin America, National Gallery Singapore (18 November 2023–24 March 2024). Courtesy National Gallery Singapore.

CBThe exhibition includes Lina Bo Bardi's iconic freestanding crystal and concrete exhibition easels, first presented at Museu de Arte de São Paulo in 1968. It was an innovative and radical way of showing art, displaying both the front and back. Why fold these into the show?

THMWe came across Bo Bardi's systems of display through our research and implemented them to enfold architecture and design into the exhibition. It was incredibly productive to work through Bo Bardi's designs and learn more about her philosophy, approach, and commitment to finding ways to display paintings without defaulting to the white wall. Her designs challenged museum-going assumptions at the time, and they're still incredibly fresh today.

Exhibition view: Tropical: Stories from Southeast Asia and Latin America, National Gallery Singapore (18 November 2023–24 March 2024). Courtesy National Gallery Singapore.

Looking at how our audiences have been engaging with these displays, there's this incredible sense of wonder that returns to the art-going experience. Going to Brazil gave us the confidence that this could be a model that could reinvigorate—as Bo Bardi wanted to do—the direct sense between artwork and viewer, as well as with other people in the museum's space.

Because of the nature of Bo Bardi's systems—the crystal easels and wooden support structures—you also see each other. People walk through and between the artworks, which was central to her philosophy, what she called 'the social function of museums'.

Exhibition view: Tropical: Stories from Southeast Asia and Latin America, National Gallery Singapore (18 November 2023–24 March 2024). Courtesy National Gallery Singapore.

CBIt's fascinating to look at the backs of paintings, it unveils what wasn't originally intended for the public. Can you elaborate on this choice?

THMA central part of Bo Bardi's intent was looking at a work of art and specifically, in this case, painting, not just as an image, but a product of labour. The back of the painting is where the canvas, stretcher, frame, and exhibition and shipping labels congeal in this incredibly solid way. Bo Bardi constructed her easels in the same way: revealing glass, concrete, and rubber.

Lygia Clark, Diálogo. Óculos (Dialogue. Goggles) (1968). Industrial rubber, metal, and glass. Courtesy Associação Cultural "O Mundo de Lygia Clark". Exhibition view: Tropical: Stories from Southeast Asia and Latin America, National Gallery Singapore (18 November 2023–24 March 2024). Courtesy National Gallery Singapore.

CBInnovative characteristics artists brought into their work in the 1950s and 60s in attempts to break free from the deemed stagnant surface of traditional art forms include kinetic art, sensorial and immersive experiences, and public participation. Could you comment on artists and artworks that aligned with this?

THMThere's an incredible synergy just talking about Bo Bardi's approach and some of the artists that we selected, including Lygia Clark. Bichos (1960s) has been a joy to have, as well as some of Clark's proposition works that integrate viewers into an experience with everyday items.

One example is Caminhando (Walking) (1963): participants are invited to take a strip of paper, glue it into a mobius strip and start cutting through the middle. When they complete one round, they have to decide whether to stop, or to keep cutting the strip into even finer tendrils. It's such an effective way to think about our bodies, and the relationship between action, inaction, and consequence.

Lygia Clark, Máscaras sensoriais (Sensorial Masks) (1967). Proposition; cotton canvas masks with herb sachets, shells, sponge, and steel wool. Courtesy Associação Cultural "O Mundo de Lygia Clark", Rio de Janeiro. Exhibition view: Tropical: Stories from Southeast Asia and Latin America, National Gallery Singapore (18 November 2023–24 March 2024). Courtesy National Gallery Singapore.

Some of these activations, along with Hélio Oiticica's works, were very important for us in thinking about activating the passive viewer, just like how Bo Bardi's systems activate us to look in different ways.

Lygia Clark's and Hélio Oiticica's works ask us to think about our bodies in different ways and almost transform into works of art ourselves. There's a wonderful saying by Oiticica that his 'Parangolés' (1964–1979) are 'wearable or habitable paintings'. I always think about that when I walk past people having fun looking in the mirror as they move and play with the 'Parangolés'.

David Medalla, Cloud Canyons No. 24. (2015). First version in series made 1964. Wood, perspex, compressors, timer, water, and detergent. 310 x 150 x 150 cm. Collection National Gallery Singapore. Exhibition view: Tropical: Stories from Southeast Asia and Latin America, National Gallery Singapore (18 November 2023–24 March 2024). Courtesy National Gallery Singapore.

CBThat makes me think about the role of art and where art happens: is it in the object or people's encounters with the object? I'd love to hear your take on that.

THMFor us, the public is very important. Going back to Clark and Oiticica, Bo Bardi and even David Medalla and his kinetic works—they are a reminder that art is a creative reflection of the time when it was made. The amazing thing about art is that it has the potential to invoke different types of creative responses across time as well. —[O]

Article From & Read More ( Teo Hui Min on 'Tropical' as Attitude | Conversation - Ocula Magazine )https://ift.tt/LDKdWaY

Entertainment

![Left to right: David Alfaro Siqueiros, Presságio (Angélica Arenal de Siqueiros) (Omen [Angélica Arenal de Siqueiros]) (1950). Vinyl on fibreboard. 100 x 83.5 cm. Gift of Don Emílio Ascárraga. Collection Museu de Arte de São Paulo Assis Chateaubriand.](https://files.ocula.com/anzax/Content/Conversations/2023/Teo%20Hui%20Min,%20Tropical/20231107JO13697HIGHRES_400_0.jpg)

![Eugenio Espinoza, Not titled (Circumstantial [12 coconuts]) (1971). Acrylic on unprimed canvas, coconuts, and rope. 150 x 150 x 25 cm. Collection of the artist. Exhibition view: Tropical: Stories from Southeast Asia and Latin America, National Gallery Singapore (18 November 2023–24 March 2024).](https://files.ocula.com/anzax/Content/Conversations/2023/Teo%20Hui%20Min,%20Tropical/20231114JO14472HIGHRES_400_0.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment